Art Therapy for BFRBs: Translating the Body's Metaphors

Similar to dreams, art can help our clients to symbolize emotions and experiences they may not be able to express in words, giving the clinician greater access to the client’s unconscious (Holmes, 2001). Not all of our clients will benefit from art therapy, but for those who have a natural relationship with art, images can provide an opportunity to explore body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) more deeply. Art can help to uncover memories and meanings that reside just outside conscious awareness and can trigger impulsive/compulseive behaviors like BFRBs. Through art, we can help our clients to reflect on their own experience and put their feelings into words, important building blocks toward an creating an earned secure therapeutic attachment.

Michelle M. has collaborated with me on this blog post. We both wanted to honor the way art therapy helped us to move through a therapeutic impasse. In a session three years into the five years we worked together, Michelle struggled to explain to me how she first discovered the power of attacking her body to calm herself. She was angry and frustrated with me at the end of the session, mad that she still wasn’t improving as a result of therapy. She told me angrily that she was was pulling “more than ever”. She went home and drew a picture and shared it with me in our next session.

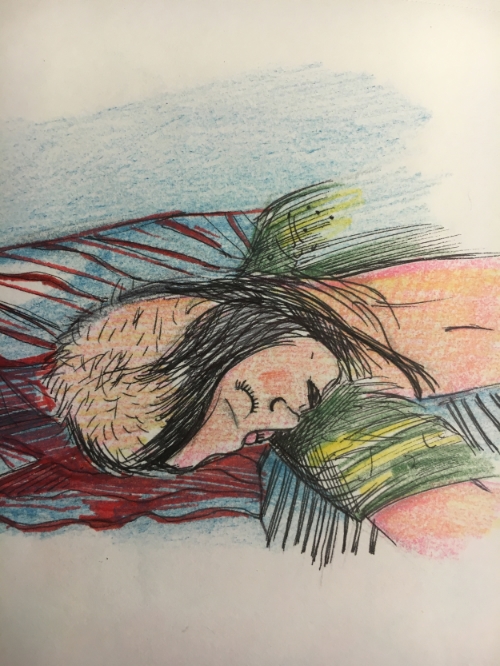

The piece (attached below) provided a clear picture of how important hair pulling was in her life, helping us both to understand why any of our gentle attempts to work on the behavior met with great resistance. Michelle was able to put into words for the first time how hair pulling had helped her survive a traumatic childhood filled with neglect and abuse.

"I made this drawing during therapy attempting to describe the feelings I had at the beginning of my pulling. I'm 12 years old in the drawing and remembering how good it felt to have something of my own for the first time. A tough period of my life during puberty and my parents divorce, I found solace in my exploration as I had with skin picking up to that time, I found a place to go." Michelle M.

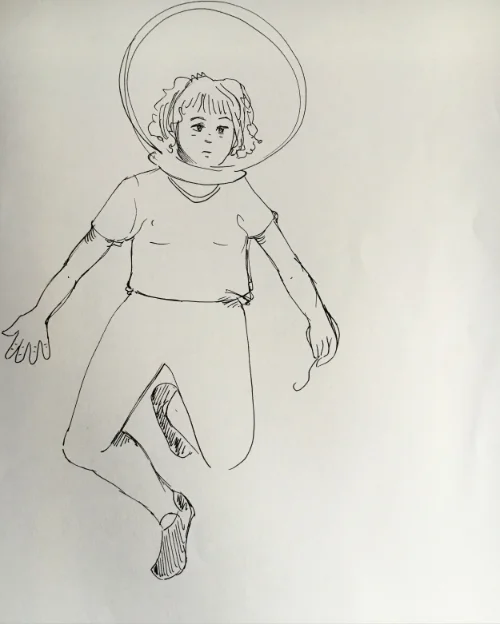

Another of Michelle's drawings captures her diffiicult-to-describe experience of dissociating during automatic pulling sessions. Here, she is floating in a space suit, with a single hair between her fingers.

More recently, Michelle has utilized her art to find acceptance for herself as a hair-puller. This self-acceptance has led her to re-enter therapy to work more on the hair-pulling behavior itself. The piece below reflects the sad beauty of her journey.

Michelle's case illustrates an important component of my work, one that distinguishes it from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The symptom-relief focus of CBT can be traumatic for those whose relationships with their BFRBs run deep. My psychodynamic approach includes a phase of safety-building before exploration of any symptoms, as recommended in the evidence-based approach of Courtois and Ford (2013). The primary goal of my work with Michelle was not to alleviate her hair-pulling symptom. Instead, my first goal with her was to build a stable enough foundation for her to begin to thrive. In our work together, Michelle internalized a more secure attachment structure, which in turn enabled her to live a more organized and satisfying life. Often, symptom relief comes when other resources are improved. Michelle's story exemplifies the fact that successful treatment does not depend on this outcome.

References:

Courtois, C. & Ford, J. (2013). Treatment of complex trauma: A sequenced, relationship-based approach. NY, NY: The Guildford Press.

Holmes, J. (2001). The search for the secure base: Attachment Theory and Psychotherapy. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis, Inc.