Guest blog post with Pavitt Thatcher

Trichotillomania and Dermatillomania: The Relevance of an Integrative Approach to Treatment

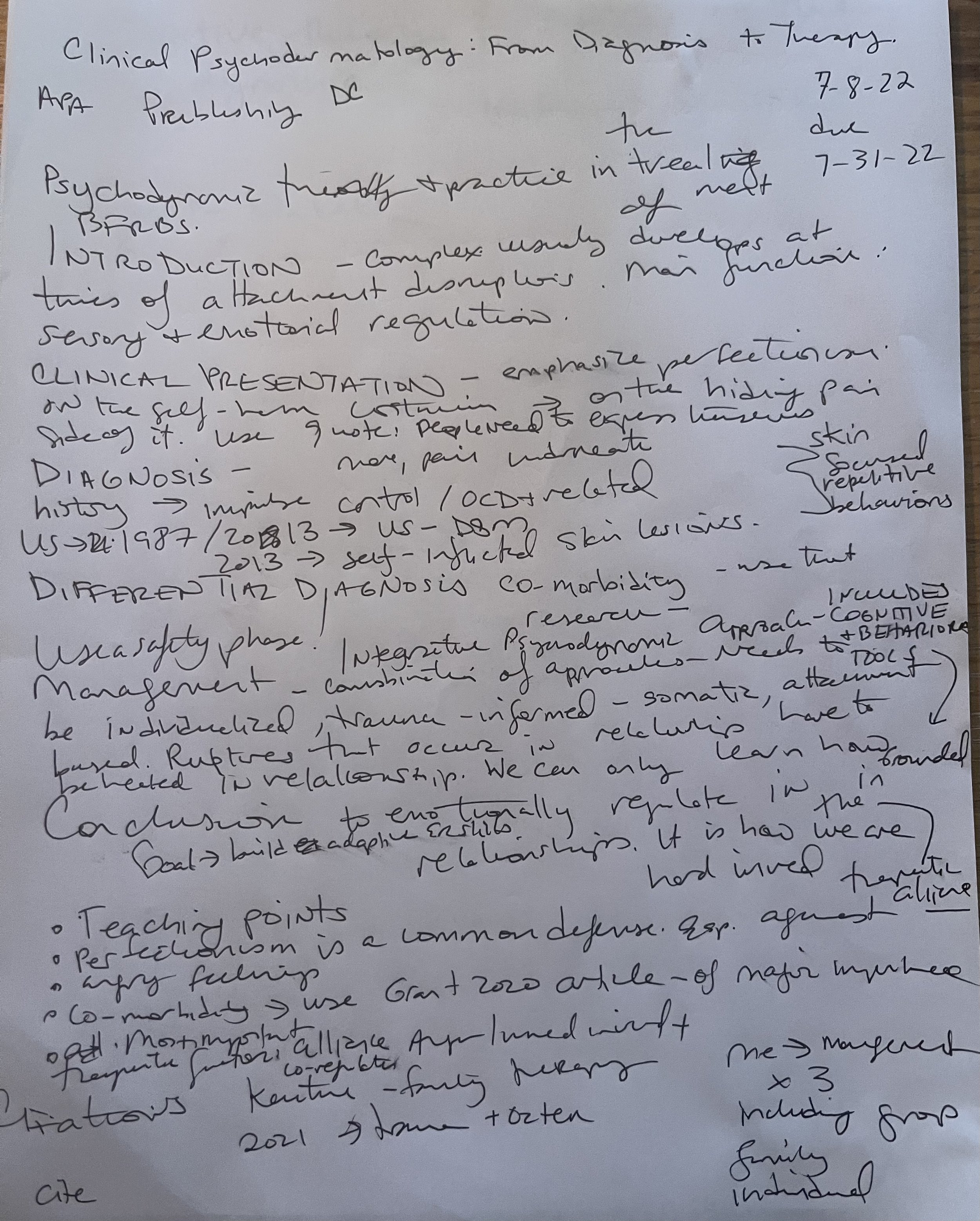

In the UK, it is difficult for people struggling with body-focused repetitive behaviour disorders to find a therapist with any training or specialisation in working with these disorders. The comprehensive cognitive-behavioural approach designed to treat this population called ComB is seen as the gold standard amongst leading clinicians.

In my opinion, some elements of ComB are essential for patients struggling with these behaviours. The program guides therapists to help patients get to know their triggers, to become aware of their sensory functioning, bodily movements and behavioural patterns that lead to body-focused behaviours. I have viewed this exploration as one of many pieces of the puzzle and a necessary component in discovering how a patient can reduce their picking or pulling.

The ComB model is an excellent starting point in one’s journey to recovery. But I felt that I needed more tools in my clinical toolbox. I found myself wondering about factors other than cognitive and behavioural may influence a patient’s picking or pulling. I have been pleased that the clinical community has advocated for the inclusion of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Dialectical Behavioural Therapy to create a more integrative treatment approach, adding in a focus on mindfulness skills, self-compassion and social skills. I have noticed other elements to consider re: how each person’s environment has impacted their behaviours.

When I considered the impact of psychosocial factors on an individual's emotional and mental well-being, I began to understand the world in which my patients live. It has become clear that trauma stored in the body is an important factor to consider, as it may be part of the clinical picture. Psychodermatologists believe that trauma may affect the body and skin and show up in a variety of different ways. There is a need to understand and perhaps re-define the definition of what trauma means and how it is understood. Many people associate trauma with a traumatic event, a set of circumstances or that ‘something has happened’. Some would argue that trauma can be seen as simply not having your needs met as a child, an unavailable parent, lack of love, lack of choices and freedom or being controlled.

This perspective has led me to appreciate an integrative approach. I think that trauma-informed care should also be part of the clinical picture. The addition of somatic therapy has the benefit of addressing a patient’s nervous system. This work includes attention to breath work in regulating the nervous system.

A psychodynamic approach to treating body-focused repetitive behaviours can complement traditional behavioural therapies. We cannot look at behaviours without asking the question ‘why’. Why do we have these behaviours erupt for some people at certain times in their lives? Psychodynamic approaches are relevant and necessary to in order to explore the conscious and unconscious mind and the stories we tell ourselves.

The theory of psychotherapy has largely come from a Western perspective, and there are limits to this perspective. The culture we come from is a filter through which we see and perceive the world; it’s a lens that shapes our relationship with others. Learning and growing up is a process of negotiation, of meeting others and of challenging our beliefs and our assumptions. As therapists, a part of our job is to scrutinize ourselves and remove any unconscious bias. Only then can we remain impartial, without prejudice or judgment. These intricacies are another part what I believe should be included in an integrative approach.

Through this wider lens, various factors come into view such as culture, religion, beliefs and core values. Ethnicity, nationality, cultural, religious, gender and diversity factors impact the particulars of each person’s engagement with picking and pulling behaviours, as do psychosocial and biosocial factors. Questions the therapist should ask include: Where did they grow up? What is their background? What are their influences? Where do they feel they belong? What does hair and skin mean to them? How do they see themselves? What are the symbolic meanings behind hair and skin in their cultures? How are our patients using their own language and mannerisms to communicate with us and each other and what are the differences that we need to be aware of?

Fundamentally, I aim to get to know each patient as a whole and understand their lived experiences, their social identity and how they understand the world around them. Ultimately, I hope that a patient will get to know themselves better and understand and reflect on themselves throughout our work together. My aim goes beyond the goal of helping people reduce picking or pulling, as I seek to address the wider issues that could influence these behaviours.

Pavitt is a UK trainee psychotherapist studying at University of London, Birkbeck. She has an MSc in psychology and has completed The TLC Foundation’s Professional Training Institute on the comprehensive behavioural model for the treatment of BFRBs. Pavitt is a co-founder of BFRB UK and Ireland. She works with clients to create a safe space in a non-judgmental, protected environment to allow people to express themselves. She is passionate and dedicated towards advocating and raising awareness for those with mental health issues. www.pavittthatcher.com